LESSONS LEARNED:

CASE STUDIES FROM THE DOE COMPLEX

Case Studies: What does Success mean from site to site?

At Rocky Flats, the primary cleanup goals were to remove the buildings, ship all of the nuclear materials and waste off-site, and enable a future use that focused on long-term protection of the natural habitat. Critical end-state interests included (1) prohibiting any redevelopment of the site, (2) protecting water quality, (3) developing and implementing a strong monitoring regime, (4) minimizing risk, (5) minimizing the DOE footprint, (6) ensuring ongoing federal ownership and management, and (7) maintaining a local DOE presence. Taken together, the cleanup activities and these seven interests comprised the end-state of the site.

The Rocky Flats end-state was feasible because the local communities, with support from the governor and Congressional delegation, recognized that the long-term value of the site did not hinge on economic redevelopment, but instead would best serve the affected communities by being protected for its abundant natural values. The end-state was feasible because Rocky Flats sits within a major metropolitan area, and thus local economies are not dependent on ongoing economic production from the site. The future use determination was to protect Rocky Flats as a national wildlife refuge managed by the U.S. Department of the Interior. That designation required congressional action.

At DOE’s Portsmouth site in southern Ohio, the cleanup project is at a different stage. Success will be defined by both what the community gets upon project completion, and the steps DOE takes to get there. Success also entails allowing certain areas of the site to be available for economic reuse. Jobs, and the ability to redevelop portions of the site and ongoing support for community development projects remain a dominant community interest. Similarly, in decontaminating and demolishing the production buildings and other critical jobs that bring the cleanup project to completion, who gets the jobs (people who live in the affected communities versus itinerant workers) and the nature of those jobs are central to determining whether the cleanup project will be deemed a success.

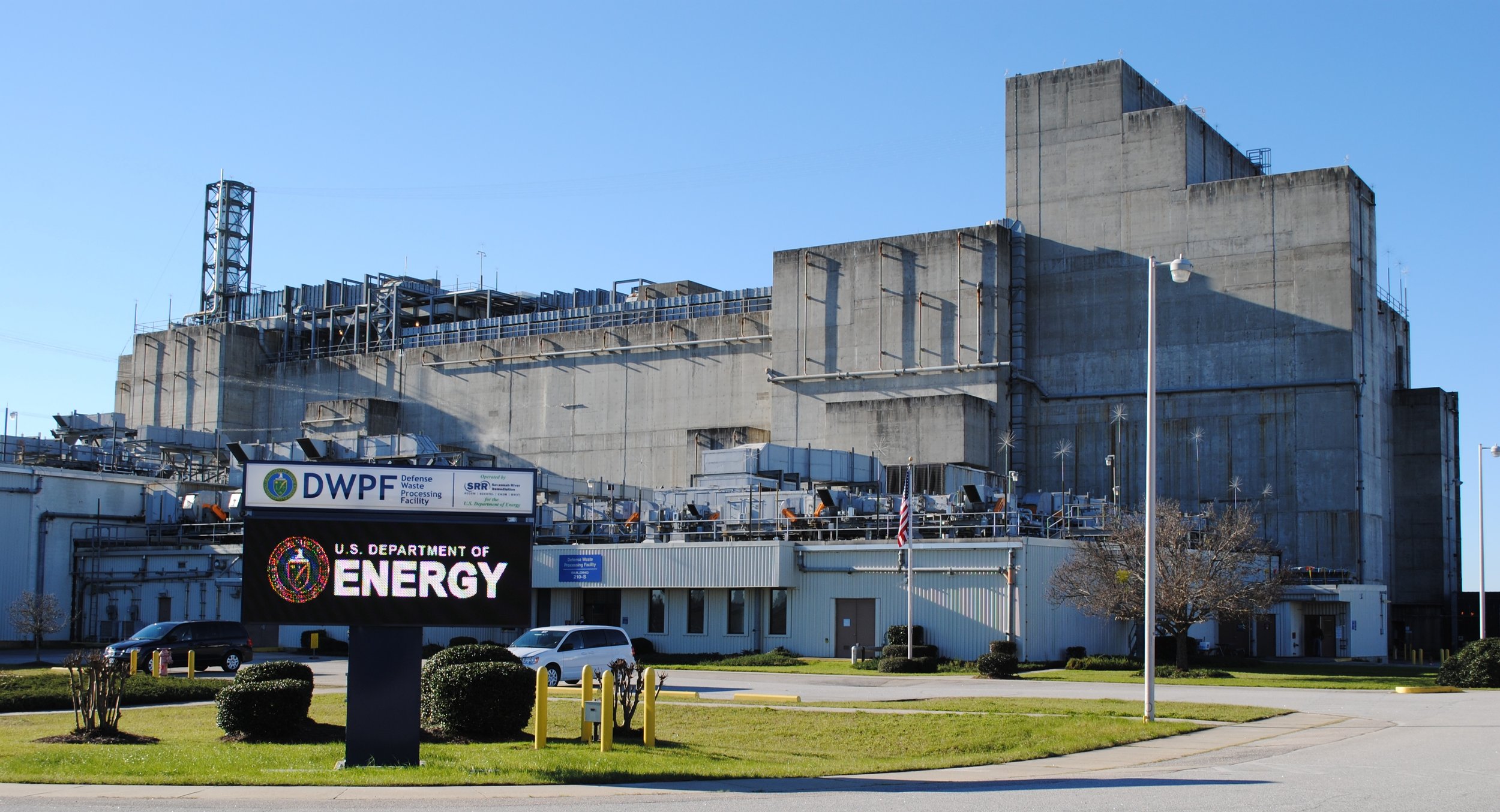

At Savannah River, Los Alamos and Oak Ridge, sites with science and national security missions, success comes within the framework of ongoing, robust federal activity. Human health and environmental concerns dominate public dialogue and the actions and activities of the federal and state regulatory agencies. At Savannah River, community priorities—and thus the definition of success—include, in part, (1) ensuring the site has an enduring mission; (2) removing waste from the liquid radioactive waste tanks and closing all the tanks; (3) continuing research on nuclear materials stabilization and processing in the H-canyon and separations facilities; (4) continuing nuclear weapons work; (5) improving the deteriorating infrastructure to ensure safe execution of site missions; and (6) supporting the construction of the Advanced Manufacturing Collaborative, an off-site innovation hub for manufacturing, fostering modern industrial practices, advancing new technologies and training the future workforce with a focus on chemical and materials manufacturing.

At Oak Ridge and Los Alamos, success is also defined by bringing together laboratory missions and ongoing cleanup activities with continued economic development activity. The suite of actions and activities required to achieve these goals requires aligning DOE’s Office of Environmental Management, Office of Science, and/or National Nuclear Security Administration, three DOE program offices with different managers and complementary but different goals.

Case Study: Scenarios for Managing Risk

Scenario #1: Should an existing landfill be removed from a site to permit reuse of the site?

When DOE announced it was closing the Mound site, the affected community that was highly reliant on the economic value generated by the federal facility positioned itself to redevelop the site, paving the way for ongoing economic productivity. Further, by selecting industrial cleanup DOE was saving time and money on the cleanup. At the entrance to the site sat a landfill that, from a regulatory standpoint, met the regulatory criteria for industrial development, but was viewed by the local redevelopment authority as an unnecessary risk and a likely negative impact on their economic development goals. Should DOE remove the landfill?

How should the Mayor respond to the proposed landfill? There are various parts to questions the Mayor is facing in this hypothetical scenario: Is the landfill worth the risk? Is she willing to accept the risk? What does she need in return to support the siting of the landfill? Is the landfill worth the political risk? ECA members frequently debate these questions. Their positions generally depend on the proximity of the landfill to the community, the waste acceptance criteria of the landfill, the alternative options available for the waste, the potential impact of the landfill on the environment, past experiences with landfills in the community, and a host of other issues.

In evaluating these and other questions, it is important to understand the regulatory framework. In general, environmental remediations are largely based on the anticipated future user and, in turn, the calculable risks to that person. Depending on the planned or projected future use of the site (or portion of the site), that person could be working in a factory, managing a wildlife preserve, or be a resident who hikes the former weapons site. Each action and each decision carry a quantifiable risk, and more likely than not, the anticipated user is one of the Mayor’s constituents.

Scenario #2: How much soil should DOE remediate, to what level, and why?

To address historic contamination prior to conveying the land to the community, DOE has undertaken a risk assessment and initiated cleanup. Under this approach, contamination will remain and land use restrictions will be required in perpetuity. DOE’s plan restricts digging in the area without the local community first hiring an environmental expert to ensure the area does not include harmful contaminants. The community, which plans to build a recreational center, including outdoor facilities, challenged the cleanup and restrictions as being unreasonable based on the future use of the site. Additional remediation will cost DOE more money and time to complete.

Environmental cleanups are also tiered towards the neighboring communities, to their concerns, values, and economic foundation. That means the agency charged with remediating the site and the agencies regulating those activities must agree on numerous issues regarding impact and risk. Those determinations include calculating what level of cleanup will ensure the agreed-to risk meets the applicable regulatory requirements, what risk level is achievable, and, perhaps most difficult, what level of risk is politically acceptable.

Case Study: Redevelopment of the Mound Site

At Mound, end-state and the future use plans were defined in terms that matched the City of Miamisburg’s economic foundation and tax base. Because of local economic factors, including competition for tax dollars, the City identified the redevelopment of Mound as foundational to its future. Accordingly, all cleanup activities (and thus the end-state) were geared towards ensuring the site would be available for economic redevelopment. However, as the parties learned through the process, DOE and the City had different interests that ultimately lead to different definitions of success. For DOE, success meant remediating the site to a level that would meet the regulatory definition of industrial use. DOE viewed success through the narrow lens of regulatory compliance.

The City, by contrast, posited that meeting regulatory standards was a given but not fully consistent with the future use of the site. Success, as measured by the City, was more encompassing than DOE’s. For the City, success was not simply a matter of remediating the site to a level that, from a risk standpoint (with controls and limitations on use), would meet an industrial cleanup standard, as defined by the applicable regulations. A successful end-state meant taking the actions necessary to permit redevelopment—and that meant remediating Mound to a level and in a manner that would permit reuse of the facility and mitigate concerns and potential risks to tenants and the community.

Case Studies: How the Budget Impacts progress at Paducah and Los Alamos

Approximately 75% of the DOE’s Paducah Site budget is for fixed (“hotel”) costs (i.e., surveillance and maintenance, DUF6 conversion, utilities, security, etc.), leaving only 25% of the budget available for cleanup, the majority of which goes towards deactivation and demolition (D&D) of four uranium enrichment process buildings. DOE’s priority at Paducah is maintaining a stable workforce in order to safely D&D these buildings. The Kentucky Department for Environmental Protection (KDEP) both supports DOE’s focus on D&D and seeks greater balance to advance the remaining environmental cleanup mission (notably, groundwater remediation). An August 2017 agreement between DOE, EPA and KDEP focuses annual budgets on demolishing an industrial cleaning facility in order to further define the largest on-site source of groundwater contamination. However, with the emphasis on D&D, critical environmental remediation projects are further delayed by decades. Therein lies the nature of the disagreement between DOE, EPA, and KDEP—the parties have different success criteria, and thus different priorities and expectations regarding how quickly cleanup should occur and the balance between D&D and environmental remediation over the next 40-45 years.

In Los Alamos County, DOE transferred land to the County. The County conveyed the land to a developer to build senior and affordable housing projects. Near that property on other property the County acquire from DOE, radioactive contamination was discovered on the land, requiring further characterization and cleanup – potentially impacting the construction of the new housing project. County officials met with DOE and their Congressional delegation to convey the importance and urgency of the cleanup and ultimately secured additional funding in the energy spending bills to address the newly discovered contamination. Identifying specific locations, costs, and benefits of the cleanup were key to gaining support from the delegation.

Photos courtesy of www.energy.gov.